The Gospel According to Casey Plett

Reading AudaciouslyLaurel Dykstra

Published 18 November 2024

Content Warning: addiction, sexual violence, murder, dismemberment

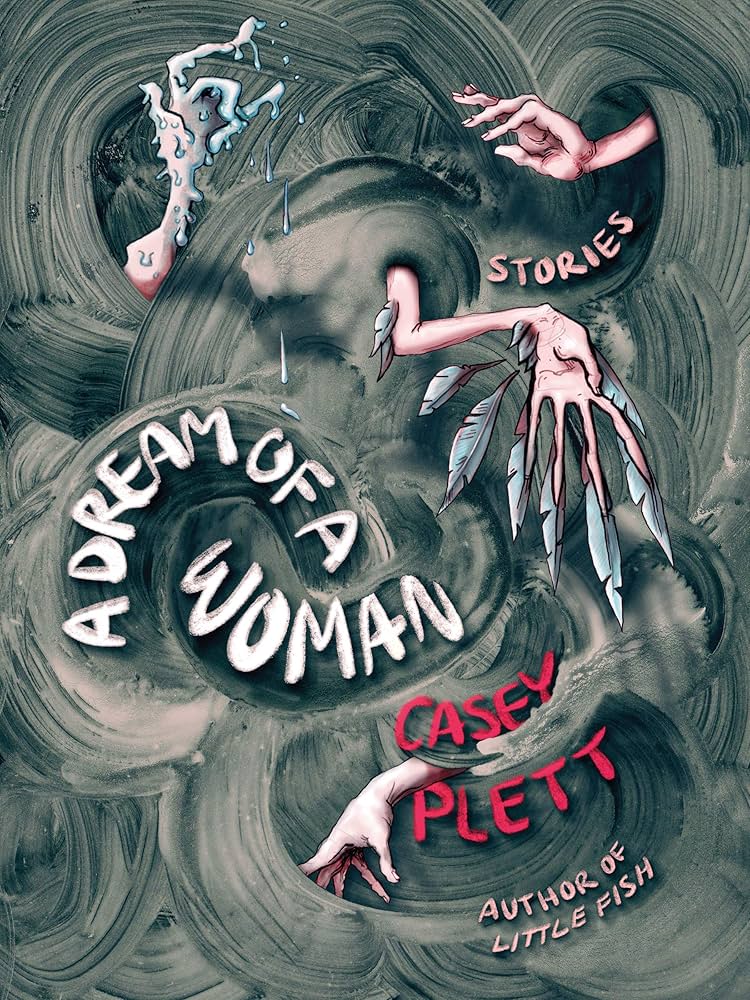

For CLBSJ’s 2024 Read-a-thon: Reading Audaciously, supporters are reading the Bible in solidarity with banned and controversial texts. I chose to read Casey Plett’s A Dream of a Woman (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021), a collection of short stories and novellas where trans women navigate home, desire, and connection in a world that both fetishizes and denies their existence.

The stories take place in Canadian cities and towns and American queer enclaves with settings and turns of phrase that are unsettlingly, neck-pricklingly familiar to me, as though some ex with unfinished business or racist uncle might round the next literary corner and catch me unawares. The book’s structure is not straightforward, characters are introduced, referenced, and revisited between stories and timelines. The longest narrative is cut into five parts and interspersed between the others.

I am reading A Dream of a Woman in this time of virulent transmisogyny (especially against trans women of colour), with the re-election of Donald Trump, sweeping anti-trans bills targeting youth in Alberta schools, and a bill in British Columbia restricting legal access to name changes. This context; the harshness of the subject matter: grief, abuse, addiction, rape, poverty, sex commerce; the juxtaposition of the stories; and cover art by Sybil Lamb and Carly Bodnar where disembodied cartoon hands, sprouting feathers, melting, raising a bottle appear out of swirling grey brush strokes visually echo the cut-up narrative, all conspired to suggest I read A Dream of a Woman alongside Judges 19-21, famously named by Phyllis Trible as a text of terror.

Set in the days when “there was no king in Israel; and every man did what was right in his own eyes,” a Levite man and his concubine from Bethlehem accept the hospitality of an old man of Gibeah. In the night some of the men of the city surround the house, banging on the door demanding to have sex with the man. Instead, the host offers the mob his virgin daughter and the concubine, “ravish them and do to them what is good in your eyes.” The mob refuses and the Levite man forces his concubine out the door where she is raped, and murdered. He then takes her body and cuts it in twelve pieces which he sends throughout the land as a call for revenge. When the Benjaminites refuse to give up the perpetrators for execution, the other tribes annihilate all but six hundred men. But then faced with the extinction of one to the tribes, they abduct six hundred young women for them.

The violence, the misogyny, the failure of hospitality, and the fracture in the passage all resonate with aspects of Plett’s book. Certainly both portray the reality of exposing to violence (whether actively or through institutions and systems) women whose status and humanity is not valued. But while the story of the concubine from Bethlehem has resonance with aspects of A Dream of a Woman, to have that be its only scriptural accompaniment both affirms the transmisogynist lie that trans people live short, violent, tragic lives and it would misrepresent the book because Casey Plett also writes trans joy and fierce hope.

In fact, it is the gospels’ stark portrait of the fractious and fallible disciples on the kingdom way that to me most resembles Plett’s writing. Her characters are tough, fragile, tender, flawed and so deeply yearning for community, particularly Gemma, Ava and Olive in the story, “Enough Trouble.”

I will leave you with some glimpses of the beloved community from the Gospel according to Casey Plett.

Open table commensality:

You have spent much of your adult life alone, not cooking meals. Olive and Ava come to the table, and you sit down and explain what you have made. You ladle gravy onto your plate and sprinkle sugar on top of the Wareniki—not too much. Traditional Russian Mennonite food is all grease and cream, you explain.

Salvation:

I have friends. A few, close, dear friends who are also trans, and I can count them on one hand. They’ve altered the course of my life, and I might not be alive without them.

Resurrection:

Gemma is beginning to understand her place in this apartment, where she might fit, the three of them. Not completely, but some blanks are getting filled in.

With this also comes a latent understanding, something Gemma has subconsciously already known: if she ever wanted to quit drinking and quit for good, she might be able to do that here. If she wanted to, she could do it here. With these two women, she could ask for their help and she could try.

Laurel Dykstra (they/them) is a CLBSJ advisory member, Anglican priest, founder of Salal + Cedar Watershed Discipleship community and author of Wildlife Congregations.